North of Ha-Rend, in the western marches of the Asentic Empire, there stretches an endless wilderness of pine savannah. The tall trees with their thick trunks seem like pillars in an endless hall, sunlight filtering

North of Ha-Rend, in the western marches of the Asentic Empire, there stretches an endless wilderness of pine savannah. The tall trees with their thick trunks seem like pillars in an endless hall, sunlight filtering down from far above. Between those pillars stretch boundless carpets of grass and fern. In that green and pleasant land there lives a people akin to the outlanders of Ha-Rend, but nomadic invasions have lightened their once-dark hair, and Asentic rule has changed their speech and customs to something softer. They call themselves Hathulians.

A Hathulian trade caravan made camp in a broad, shallow valley where a wide creek flowed. They were one of an endless stream, passing from gentle Hathulia to the savage western coasts, to the wilderness of the northern lumber camps, and back with precious goods. It was this passion for trade and harvest in the distant lands of the utter west that made Hathulia a jewel in the crown of the Asentic Empire.

The caravan was returning from a delivery of supplies to the lumber camps in the northern hills. They were still some miles from Harnea, with its Asentic legions keeping watch over the Volaki frontier. Still, the merchants were at ease, gathering around a central fire, their wagons circling them round, swapping stories and singing songs. Their guards made camp outside that circle, and sent patrols sweeping out to the crests of the low bluffs on either side of the creek, their booted feet crunching pine needles and leaving soft prints in the grass.

So it was that Soshana felt safe in her wanderings, and came alone to the banks of the quiet creek. Her father, one of the merchants, had warned her always to return to the camp before sunset. The water was cool, though, and clear, and she had ridden long in the thick heat of a southern summer. The music that water made as it bubbled over the little rocks was enchanting, and it would be three weary days before they reached their destination. She could not help but linger a little longer, enjoying this brief respite.

The scream was cut so short, she almost thought she had imagined it. It had come from the distant bluff on the other side of the water. Maybe she had imagined it. The guard had ridden out in force along the route of their patrols before settling in. No threats should remain to harass the lonely soldiers that now walked the outer lines.

So she reasoned, and dismissed the sound as a figment of her imagination. But in the gathering gloom of an early forest twilight, she saw something she could not dismiss. A child, she thought, making its way through grass toward her. What was a child doing here?

“Hello?” She called, “Are you lost?”

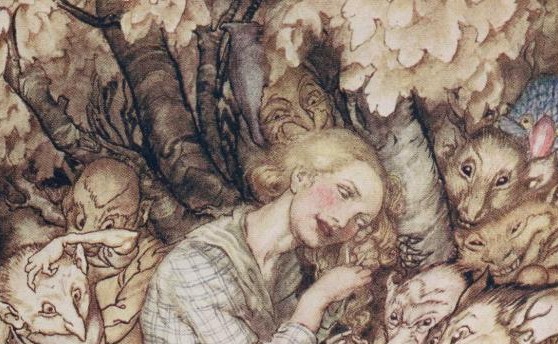

She thought she heard laughter. It was too low and coarse for a child’s. The figure continued its approach, and she saw that though still small, it was hunched over, and clearly larger than it had seemed. It had a too-broad head on a long-limbed, spindly frame. She stood and backed away from the water, hurriedly thrusting her wet feet back in her boots and tying the laces.

“Where you go, Eb-glon mon?” the thing croaked. She could see it clearly now, emerging from the grass and sliding down the far bank to the water’s edge. The thing had mottled yellow-green skin, a toothy smile that squatted like a toad below slit, serpentine eyes, and long, lank, greasy hair. It padded along the shore, but did not cross, raising a clawed hand in mocking greeting.

She screamed.

Soshana raced through the forest, skirts held in her hands as her legs moved faster than she ever knew they could. Like a deer, she sped through fields of fern and leapt over fallen trunks, her heart pounding as she did. Darkness gathered round her as the circled wagons drew near. Just outside them stood a tent, a fire before it, and a small knot of guards. One of them stepped toward her. She flung herself in his arms.

“Help me!” she screamed. “Help me! It’s behind me!”

“What’s behind you, girl?” came a gravely voice. She looked up into the face of Dowan, a gray-haired old veteran that had been in her father’s service since she was a girl.

“I don’t know. It was evil.”

She spun around to look. The gray of twilight had begun to deepen to a dark purple. She saw nothing but the endless trunks of trees. A horse nickered nearby.

“Where is it?” she asked. Her voice was pitched high, still more than half panicked.

“I don’t see anything,” one of the younger soldiers said. “What are you scared of?”

The padding of feet on shifting pine needles rose gently in the darkness. Soshana began to whimper. She had always been brave, and would have felt ashamed were she aware of the noises she made, but terror had washed all self-awareness away.

“Draw blades,” Dowan said. “Soshana doesn’t run from shadows.”

Half a dozen swords were drawn without hesitation, their edges glinting in the orange of the firelight. There were dark shapes now, in the midst of the trees. Small. Childlike.

“Who goes there?” Dowan demanded.

“Are they children?” the younger soldier asked.

Soshana felt the hair rising on her neck, felt the terror seizing her once again. One of the shapes emerged into the flickering firelight, jaws dripping with saliva, and the soldiers cursed. She ran to the sound of the nervous horses, screams of blood and death rising behind her.

Great beginning. I liked the difference between the first compassionate thought of the small stranger being a lost child, and the hideous and (to the reader) unknown terror that it turned out to be.