In his long journey home, Odysseus was forced to pass between the fearsome monster, Scylla, and the vast, ship-swallowing whirlpool, Charybdis. A similar danger confronts anyone tasked with describing the origins of John W. Campbell’s

In his long journey home, Odysseus was forced to pass between the fearsome monster, Scylla, and the vast, ship-swallowing whirlpool, Charybdis. A similar danger confronts anyone tasked with describing the origins of John W. Campbell’s classic novella, Who Goes There?

On the one hand, the connections between this story and H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness seem telling. The Lovecraft novella was published in Astounding Stories in 1936. In 1937, Campbell was put in charge of the magazine, which he renamed Astounding Science-Fiction in March of 1938. In August of that year, he began publishing his own Antarctic horror serial under a pseudonym. Both his and Lovecraft’s featured scientists exploring the frozen continent, a subsection of the expedition uncovering the remains of buried alien life, and the subsequent death by monster of most of those involved. The monsters themselves have uncanny similarities.

On the other hand, while Campbell had almost certainly read At the Mountains of Madness, he nowhere mentioned it as an inspiration. His own story is far from a mere ripoff–it is a chilling tale of a kind very different from Lovecraft’s. There is no lost civilization, and the human protagonists do not wander about the icy wilderness or explore ancient ruins. They are trapped inside the base with a creature they cannot comprehend, struggling less to understand than to survive. It is a far more claustrophobic, creature-centered narrative, and it is no wonder Hollywood found it easier to adapt than Lovecraft’s sprawling, almost ethnographic survey of Elder Thing civilization. This story stands on its own.

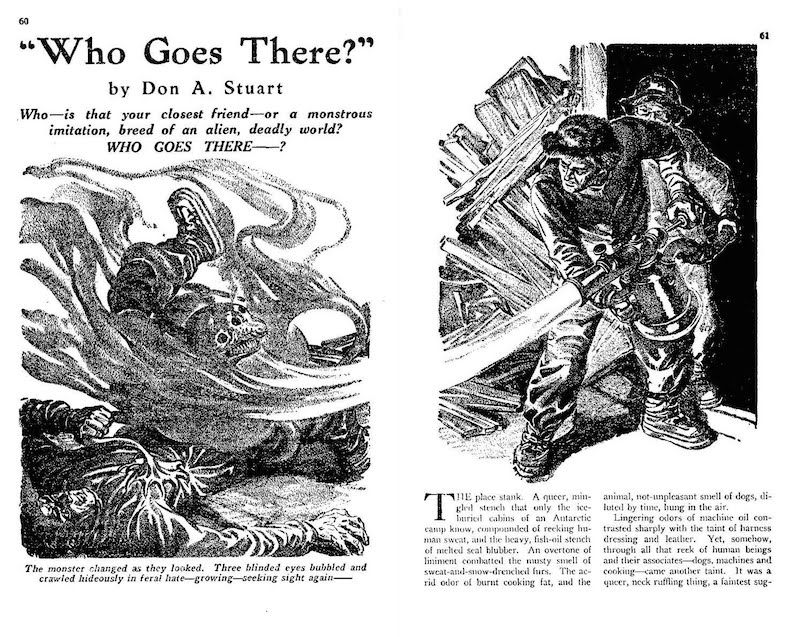

Where the two come closest is perhaps the creature at the center of Who Goes There? When found, it has “three red eyes” and “blue hair like crawling worms.” One of the scientists, Blair, thinks it is possible, though not likely, that this is not its original form. Whatever that may have been, its true nature is revealed when, once thawed, it attacks one of the camp dogs:

“The thing we found was part Charnauk, queerly only half-dead, part Charnauk half-digested by the jellylike protoplasm of the creature, and part the remains of the thing we originally found, sort of melted down to the basic protoplasm.”

Like Lovecraft’s shoggoth, the Thing is fundamentally a mass of roiling protoplasm, growing misshapen limbs at need. But where the shoggoth stayed in this form and only imitated the speech of its masters, this creature is capable of imitating a person’s entire body and behavior, and even infecting them, turning more and more living beings into duplicates of that horrid alien life.

But Campbell’s monster is Lovecraftian in more ways than one. Not only does it resemble a particularly vicious shoggoth, it also takes on aspects of Cthulhu:

“That creature wasn’t dead, had a sort of enormously slowed existence, an existence that permitted it, none the less, to be vaguely aware of the passing of time, of our coming, after endless years. I had a dream it could imitate things.”

As in The Call of Cthulhu, the dreams of the deathless sleeper are no accident. It is clear that the creature has telepathic abilities. The sensitive among the scientists have visions of the creature’s intentions while they sleep, and all of them are exposed to its mind-probing powers even when awake. It knows their plans, can anticipate their every move, and will use this to destroy not only the expedition, but every last shred of Earth-life.

Campbell’s beefed-up shoggoth justifies the story on its own, but he adds a less Lovecraftian element that gives it even more flavor. The heroes of Who Goes There? are not frail, bookish men doomed to madness at the first sign of danger. “Second-in-Command McReady,” the team’s meteorologist, is “a figure from some forgotten myth, a looming bronze statue that held life, and walked.” Vance Norris is their physicist, and “If McReady was a man of bronze, Norris was all steel.” Everyone in the story is a giant of a man, molded out of metal, stockily built. They are men of action. At every turn they risk their lives to preserve the planet, or else to protect their comrades in arms from the monster that stalks them all. Madness does come, but it does not find these men easy prey.

This story is well worth your time. It’s packed with survival horror, speculative science, and plenty of fire and blood and heroism. For fans of John Carpenter’s 1982 adaptation, much will be familiar. There are startling differences, however, and some suggest very different movies that could have been made.

There are multiple versions of Who Goes There? available. The original, twelve chapter version was used for this essay, though it is currently hard to get. One with fourteen chapters was published for later collections, and is currently easier to get your hands on. More recently, a full, previously unknown novel was discovered and published as Frozen Hell. It seems Campbell had to cut this story down to make it fit in the magazine.

Our story, however, will keep expanding like a protoplasmic mass, leaping from the pages of the pulps to the silver screen. We will return to the cold wastes in a week with 1951’s The Thing from Another World.