For earlier chapters in The Book of the Prophet Joshua, look here: 1. Despite the unholy terror which woke the goats with the morning, the flock was calm and compliant as Adam led them out

For earlier chapters in The Book of the Prophet Joshua, look here: 1.

Despite the unholy terror which woke the goats with the morning, the flock was calm and compliant as Adam led them out of the ruins and into the sunlit streets. The two travelers continued their journey. Buildings grew taller as they went, their tops towering among the clouds, only to shrink as they left the once-great market center behind. Hours stretched into days, and the Scourged Lands faded into the west, replaced by the verdant prairies and forested creek bottoms of the untouched East.

One morning, near the end of their journey, they stopped on a high muddy bank overlooking a swift-running creek. Joshua sat on the edge, singing strange words, borne on a haunting melody.

Adam listened as he considered how to get his goats down to the water. “What are you singing?”

“A hymn.”

“What language?”

“A dead one. Forgotten, unless some other prophet speaks it.”

A kid came up to Joshua, rubbing his head against the man’s dirty shoulder. The prophet reached out his big hands and scratched it behind the ears, singing again. Satisfied with a brief moment’s attention, the little goat slipped away, walking along the edge of the bank. It was a steep drop, maybe twice the height of a grown man. Adam watched, nervous.

“We shouldn’t stay long,” Joshua said, “I was told to keep going.”

Adam was silent for a moment, still unused to having his path directed by the voice of the LORD.

“Alright. Let me get them a drink, and then we can go on.”

“Alright. A little longer.”

Just then, there was a panicked bleat from the kid as it stumbled over the edge and tumbled down into the creek. Adam swore, grabbed an overhanging root, lowered himself off the rise, and dropped to the muddy creek bottom. The kid bolted downstream and around a corner.

The goatherd swore.

Joshua frowned as he peered down at his companion. “I can’t stay long.”

Adam swore again. “You go ahead. I’ll beat double time when I get the chance and meet you somewhere.”

“I’ll be following the road to Corsican land, at the turn towards Nindad, on this side of the river. I’ll wait there till the next moon, unless the LORD calls me elsewhere.”

“Sounds good. Stay safe.”

Then Adam was gone around the bend.

***

Joshua continued, going southeast, to land once worked by men, now grown wild and wooded. Rumors told of an old tribe who once dwelled there, who called themselves Corsicans. They were a band who had survived the Scourge. But the Wind Sickness caught them, and they were warped in mind and body. They threatened the few who traveled west along those roads, but the people of Hadochee gathered to drive them back into the forest. They were said to have died out long ago.

On the road through Corsican lands, there was a trail, barely wider than a deer path, that went off to the right, into the woods. Joshua stopped by it and listened. Down the narrow lane echoed the sobs and shrieks of a small child. He left the road without a moment’s hesitation and dove into the woods, racing through bramble-choked alleys and leaping over potholes and roots. He shot out into a wide clearing, the drought-dry crop rows of a sun-scorched farm. An emaciated woman lay in the path leading to the house. A starving boy, barely old enough to walk, sat screaming beside her motionless form.

Joshua rushed to the child, who was badly sunburnt, with cracked lips. He spoke soothing words and gave the boy a long draught from his water skin. Then he leaned over the still mother, brushing away flies, and laid his ear on her chest. He heard nothing, but when he set the back of his hand before her mouth, the fine hairs there were shifted by a gentle breath. She was alive, barely.

Once he had carried them both back into the dusty, two-room building, he stood out on the porch and gazed at the fields, and the woods beyond. He had not noticed before, but all the vegetation in the region was brown and withered. There had been a long dry spell in his absence. The land had suffered, and the people with it. For a quiet moment he prayed, then took a bucket from off the porch and stood in the yard. It started to rain.

That night he poured water through the cracked lips of mother and son, followed by a thick broth of quail. The woman woke just enough to keep from choking, but the child swallowed the soup with such eagerness that Joshua had to take the bowl away to keep him from scalding himself.

When he had settled them both into bed, the prophet went outside again, and walked about the property. He found an old henhouse, long unused, and a shotgun with a broken trigger leaning against a rusty old smoker. A dry well stood on the other side of the house. Beneath a tree, by the edge of a weed-choked field of dead, half-grown cornstalks, he found two graves. One was well cared for, marked by a gravestone. The other, with newly turned earth, was shallow and marked by a crude wooden cross.

The next day seemed to last a year. He fed them, he gave them water, he cleaned them when they soiled themselves. It was hard to tell when the woman knew what was happening, but it was long before she had the strength to tend to her own needs. She wept often, but only when she was conscious.

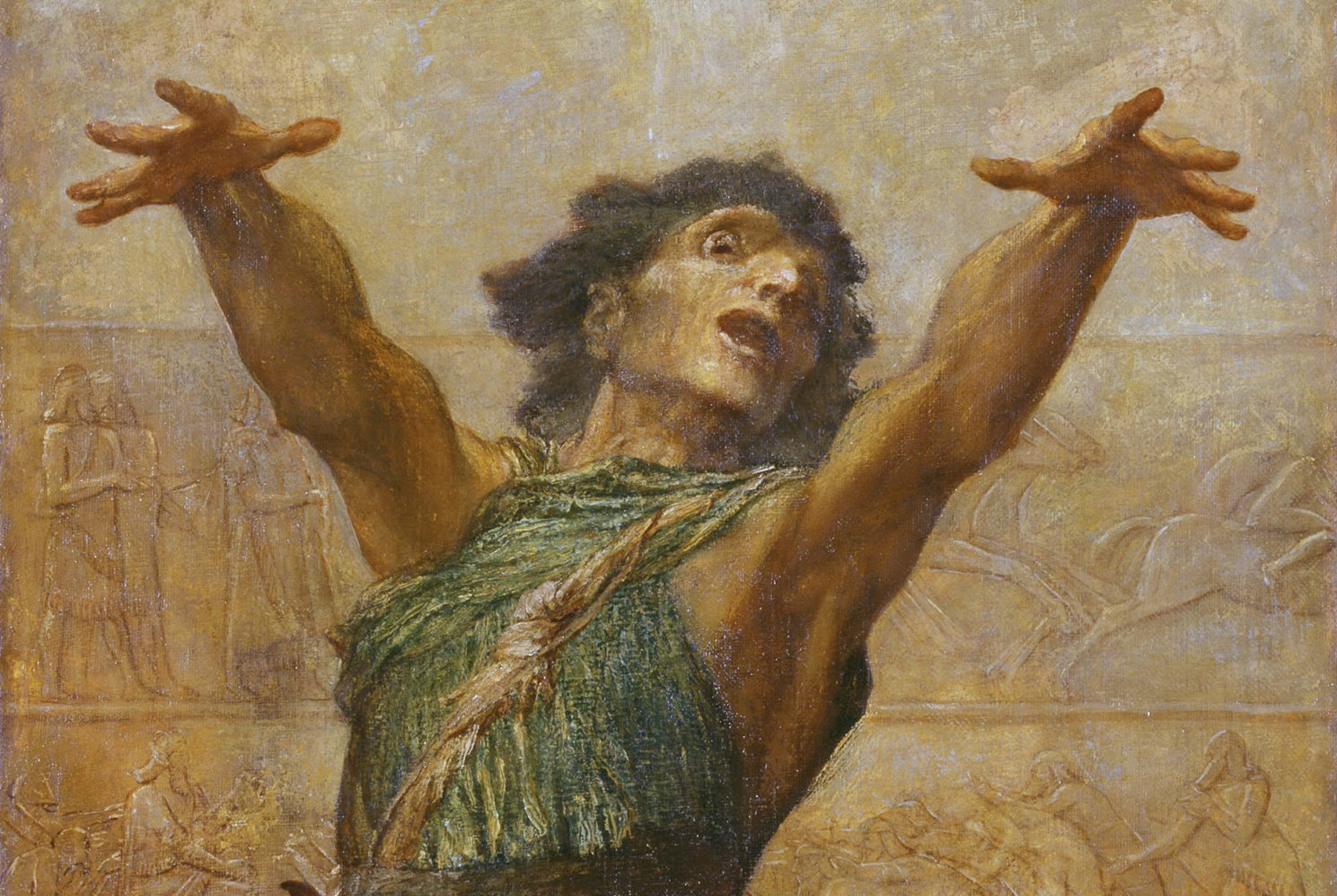

In the night, Joshua sat alone before the fireplace, his bowl empty and cool. The LORD provided. The prophet looked down at his hands, scarred and calloused. He had tended the sick before, and it always made him feel helpless. But that had been before the signs, the wonders. That had been before he was called. The LORD had given him power, and he had lain hands on the blind and the crippled, the dying and the insane. All had been healed. But not these two. Whatever power had been given to him, it would not work for them.

“LORD, how long? If you will it, you can heal them in a moment. But they suffer. The child’s pain… he whimpers in his sleep. And his mother won’t look me in the eye. Why do you drag this out? Why put them through this?”

The wind whistled through the cracks in the walls. The fire popped, giving birth to a small cloud of sparks. The LORD did not answer. Another did.

“Why indeed. Maybe he’s busy.”

Joshua’s shoulders slumped.

“Get behind,” he muttered.

“I’m always behind you.”

And that was all. The night was as silent as before.

“I don’t understand. But whatever you tell me, that will I do.”

In the corner, the woman’s eyes were open. She did not hear the LORD respond. She had not heard the other. But she heard Joshua speak.

“But why? No–I don’t need to know. Yes, LORD. I will do it.”

He stood and turned to look at his charges. Their eyes were closed.

* * *

Over the next few days, the prophet nursed the woman and her child back to health. Soon, she was strong enough to speak.

“I’m Sarah.”

Joshua paused, holding the spoon over the steaming bowl.

“And the child?”

“His name is John.”

“I’m glad to know you, Sarah. My name is Joshua.”

She nodded weakly and looked at the spoon. He fed her. When he was done, he went to the pot to fill a bowl for himself. He sat beside her while he ate.

“I hope you don’t mind.”

She laughed a little, and almost choked. Then tears fell.

“What’s wrong?”

“You’re a holy man?”

His brow furrowed. “I serve the LORD.”

“Did he send you?”

“Yes.”

She sobbed.

“Please,” she said, “take my son.”

“I don’t understand.”

“God sent you to take him from me.”

“He sent me for you both. What’s wrong, Sarah?”

She would not meet his eyes.

“What’s wrong?”

“I’m a coward,” she sobbed.

“A coward?”

“I wanted to do it. I couldn’t. And if I had–”

The rest was swallowed up in tears. Joshua just looked at her. Then the child crawled up out of his pallet and clambered into his mother’s arms. His skin was red and peeling. The sunburns had been horrific. His dehydration had been worse than hers. How long had he lain out there beside his starving mother?

Joshua stiffened. He stared hard at Sarah. For days now, he had nursed the two of them in the shelter of the little cabin. It was a pleasant place, with a wide porch wrapping all the way around. Yet he had found them laying in the open.

“It was the LORD that stayed your hand,” he said. “Burns heal.”

* * *

As the boy regained his strength, Joshua showed him how to help his mother. In the mornings and evenings they would gather rain and heaven-sent quail. They smoked and set aside a growing stock of dry quail. He was so very young, but eager to help.

The day came when Sarah could stand, and even walk about the house unaided. Joshua prayed over her. Then he took up his staff and looked to the east.

“Why are you going?” she asked.

“I have to go home.”

“Why? Did God tell you to?”

He turned to look at her. She turned her eyes away.

“I heard you praying.”

“Yes. He told me to go home.”

“Then take us with you.”

“You’re not strong enough yet.”

“He is! Please, don’t leave us. You saved us once, but if we don’t leave, we’ll starve again in a few weeks. We need you.”

The boy heard the distress in his mother’s voice and rushed to hug her.

“It was the Lord’s hand that saved you, not mine.”

“Then take him to the land of your God, to his people. Your God should be his God. Teach John to follow his ways, not mine.”

“I’m not taking him from you. I can’t. And I can’t wait while you heal. I have to go ahead.”

Her eyes filled with tears, and he reached out to wipe them away.

“Listen to me, Sarah. Daughter.”

She met his gaze.

“I am going to call the people to repentance. I am called to make them faithful to the LORD. But when I leave here, another will come behind me. He will guard you and keep you, and when you are ready, he will take you to the land where I am going. Trust him as you trust me.”

The tears fell, but her hand drifted down and settled on the head of her son.

“So you will not be afraid when I go, I will leave you a parting gift.”

He helped her out of the bed and across the room. Then the prophet and the broken family stumbled out the doorway, into the foggy evening air.

“Watch,” he said, and whistled.

There was a moment’s silence, then a cacophony of clucking and squawking as a flock of chickens burst from the woods and made their way down the path to the porch.

“I’ve repaired the henhouse.”

There was a second din of squeals and snorts, and a drove of hogs trotted down the road after the birds, congregating peacefully a few feet from the startled woman.

“I also built another pen. The feed bins are full. When my friend comes to take you to Hadochee, bring these animals with you. It will be a foundation for your prosperity.”

The woman turned and embraced him, more tears sliding from her eyes.

“Thank you,” she said.

“The LORD be with you, my daughter,” Joshua replied, and stepped off the porch and onto the path. The boy was already down among the hogs, chasing the unusually docile animals back towards the pen. He stopped for a moment and looked Joshua in the eye. Joshua waved and carried on.

Once on the road, time passed swiftly once more. The miles slid away beneath Joshua’s feet, until at last he came to a wide river in the dark, with moon and stars upon the water.

* * *

The next day was long and hot. The woman sat on the porch, and the boy played in the dirt, building worlds in the sand. Chickens clucked, pigs snorted, and somewhere birds were singing. The buzz of cicadas filled the air. Green grass grew on the graves of Sarah’s father, and the father of her child.

Then came another sound, a vulgar whistle from the path back to the road.

She ran to John and scooped him up. As she rushed inside and closed the door, Sarah caught a brief glimpse of howling, laughing men riding towards the house, swords, axes, and muzzle loaders in hand. She barred the door.

“Come out, woman! Say hello!” one of them shouted.

“Yeah,” said another, circling the shack, “Show some hospitality!”

Then a third said something else, something far fouler, and her heart stopped as she looked at her frightened child.

“Go away!” she screamed.

“But we just got here,” said a voice on the porch.

She took a long knife from the mantle and looked at her child again. Her knuckles were white on the handle. She couldn’t let anything happen to him.

The man on the porch crashed into the door, but it held. John ran to her. She held him tight, the knife’s blade stretched along his little side. She knew what she had to do. An axe smashed through a window shutter, another slammed into the door.

“It’s going to be okay,” she whispered, pushing the boy back a little and fumbling with the knife. But when he looked into her eyes, trusting her again, her heart failed. The axe thudded again, and the door burst open. She turned from her son and rushed at the intruder.

Thunder. The sound split the air and blood splattered her face, her dress, warm and wet and smelling of copper. The wild-eyed man fell backwards, and the half-splintered door swung closed again.

“She has a gun!”

There was a second crack, and the axe-wielding man at the window went silent.

“It’s coming from outside! Spread out, find him!”

Boots scuffed on the dirt outside. Sarah clutched John to her chest and pulled him into the corner. Pigs squealed in distress. Someone sprinted along the side of the house and a hoarse cry was cut short by the sound of wood striking flesh. It came again and again, and bone crunched. More boots ran in that direction.

“Randy!”

“Where did he go?”

“Over here!” shouted the third man from the opposite side of the shack. There was a clash of wood on wood, and again wood on bone and flesh. The man screamed. His companions cursed as they ran to his aid. Something whistled through the air and a heavy body fell to the earth. Then silence.

“Go.” The voice was rough. “Go now, or I’ll come for you.”

There was no reply, just the sound of running feet, a horse whinnying, and hoof beats fading into the woods. Then more boots up the steps and across the porch. The door swung wide beneath a dirty hand. A man’s shape was on the threshold, backlit by the sun.

“Are you alright?”

The woman nodded. The goatherd set down his gun.

* * *

The sun set again, and the moon rose over the woods. Joshua sat on the riverbank, waiting.

6 thoughts on “The Book of the Prophet Joshua – Chapter Two”